Second Class

California's undocumented workers build our houses, wash our cars and clean our gyms. But they often lack the basic health and safety protections that are every worker's right.

Text by Alex Nieves

Visuals by Anne Wernikoff

Without them, California couldn’t be what it is today.

The Golden State may be best known for Silicon Valley and Hollywood, but its 2.2 million undocumented workers—10 percent of the workforce—help power the world’s fifth-largest economy.

Without legal status, they must take jobs that are physically taxing or outright dangerous. More than half of the state’s roofers, janitorial workers and cooks are noncitizens, according to the U.S. Census. About a dozen other job categories, from tree trimmers to drywall installers, are filled largely by undocumented workers.

The vulnerability of this workforce is well known. California has extended workers’ compensation benefits to undocumented employees, passed laws prohibiting employers from using immigration status to retaliate against them and banned reverifying an already-hired employee’s work authorization.

Yet labor rights advocates say undocumented workers’ rights are still being violated. Worse, they say, the Department of Industrial Relations (DIR), the state agency tasked with protecting workers’ rights, has insufficient staffing and funding to rein in bad employers and educate workers about their rights.

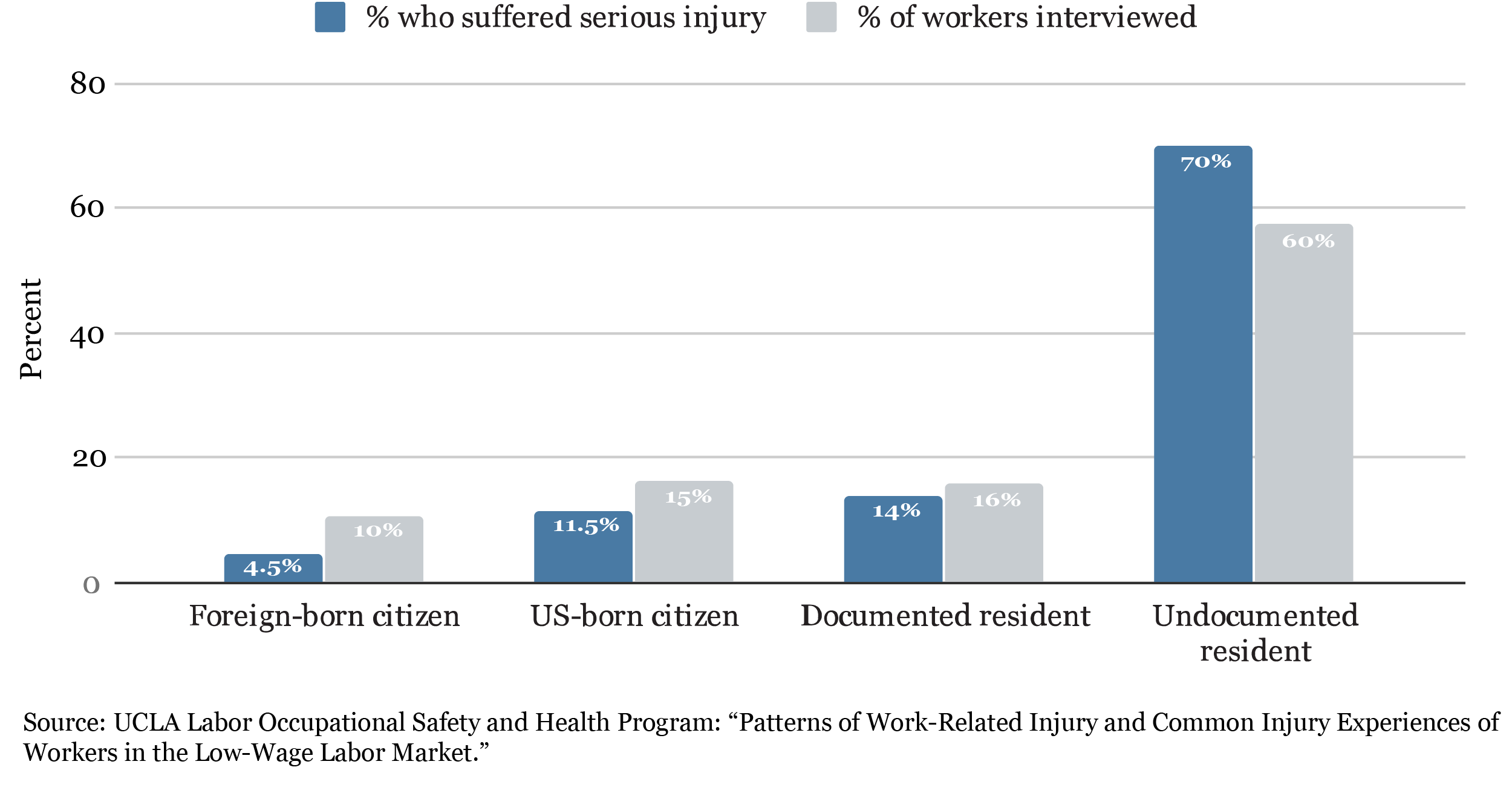

As a result, undocumented individuals are simultaneously more likely to be injured on the job and less likely to receive worker benefits than any other group of employees.

Injury rates by nativity/immigration status

What follows are the stories of two California undocumented workers and a labor organizer that reveal the challenges they face, and the story of a state legislator trying to fix the problems.

Hurt on the Job

For years, Yolanda Urioste worked a grueling schedule cleaning gyms around the East Bay. Over the course of a 9-hour workday, she would bounce between 24 Hour Fitness gyms in Oakland, Hayward and San Leandro, mopping floors and wiping down hundreds of machines.

Yolanda Urioste working at a 24 Hour Fitness gym in 2017. (Photo courtesy of Yolanda Urioste)

At first, the job was a welcome opportunity to work after recovering from abdominal cancer. The 50-year-old mother of four still had a 10-year-old daughter to take care of and rent to pay on a small apartment in Oakland’s Fruitvale neighborhood.

Her employer, Kellermeyer Bergensons Services (KBS)—at 12,000 employees, one of the largest janitorial contractors in the country—also hired her son Pedro to work alongside her as a two-person team.

Before long, the work started to take a serious toll on Urioste. The repetitive motion of scrubbing machines and buffing floors led to severe arthritis in her right middle finger and sciatica nerve pain in her lower back, chronic injuries that plague many janitorial workers.

The injury that caused her relationship with KBS to unravel initially didn’t seem like a big deal. “It all started when a machine fell on my foot in 2017,” Urioste said. “A machine fell on my toe and I lost a nail.”

Minutes later, crying from the excruciating pain, she called her KBS supervisor, who asked if she was going to complain or keep working. She knew there was only one correct answer.

“I kept working for three months with my foot swollen,” she said, pointing to her right foot. “I just took the shoelaces off of this foot. And I was working, hobbling, hobbling, sitting, cleaning the bathrooms, doing everything.”

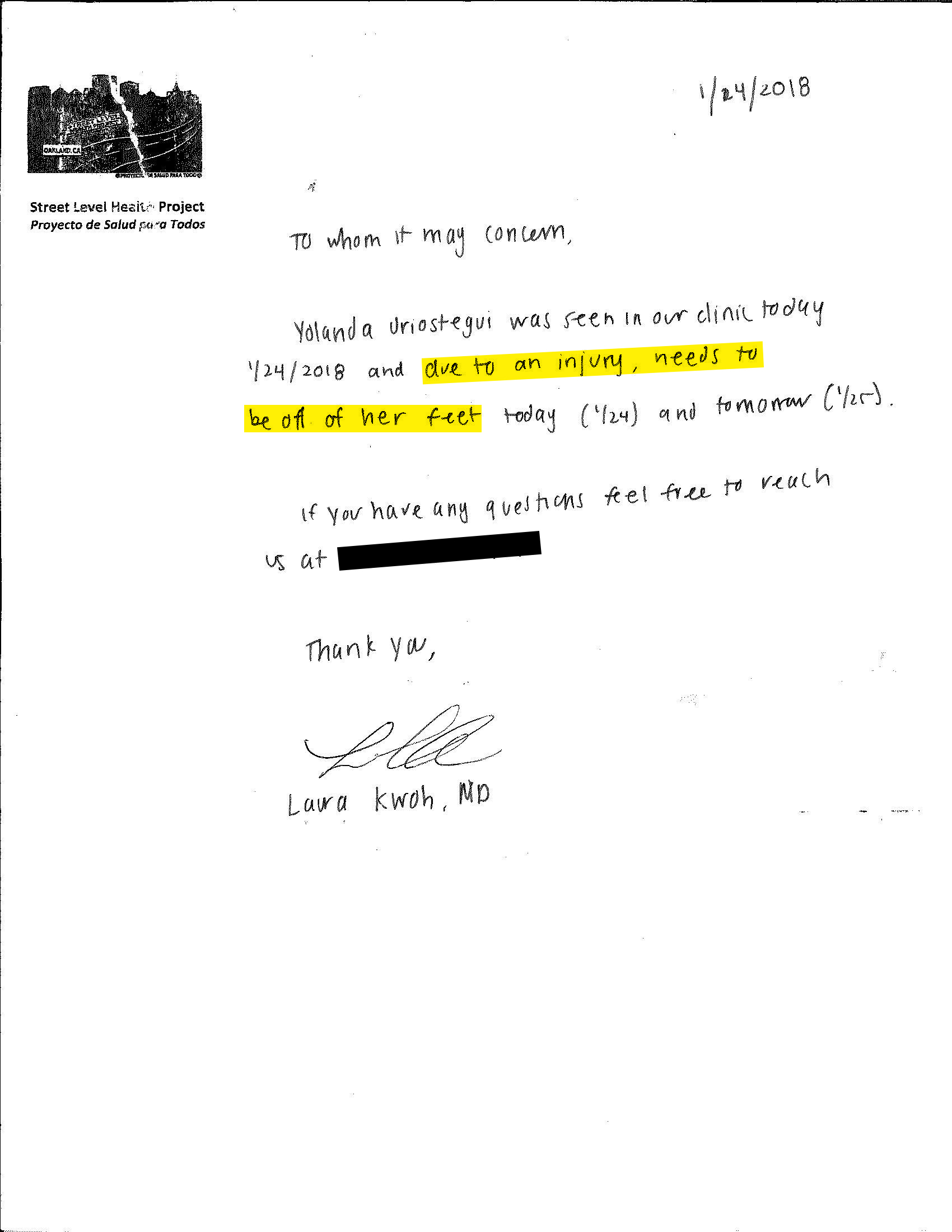

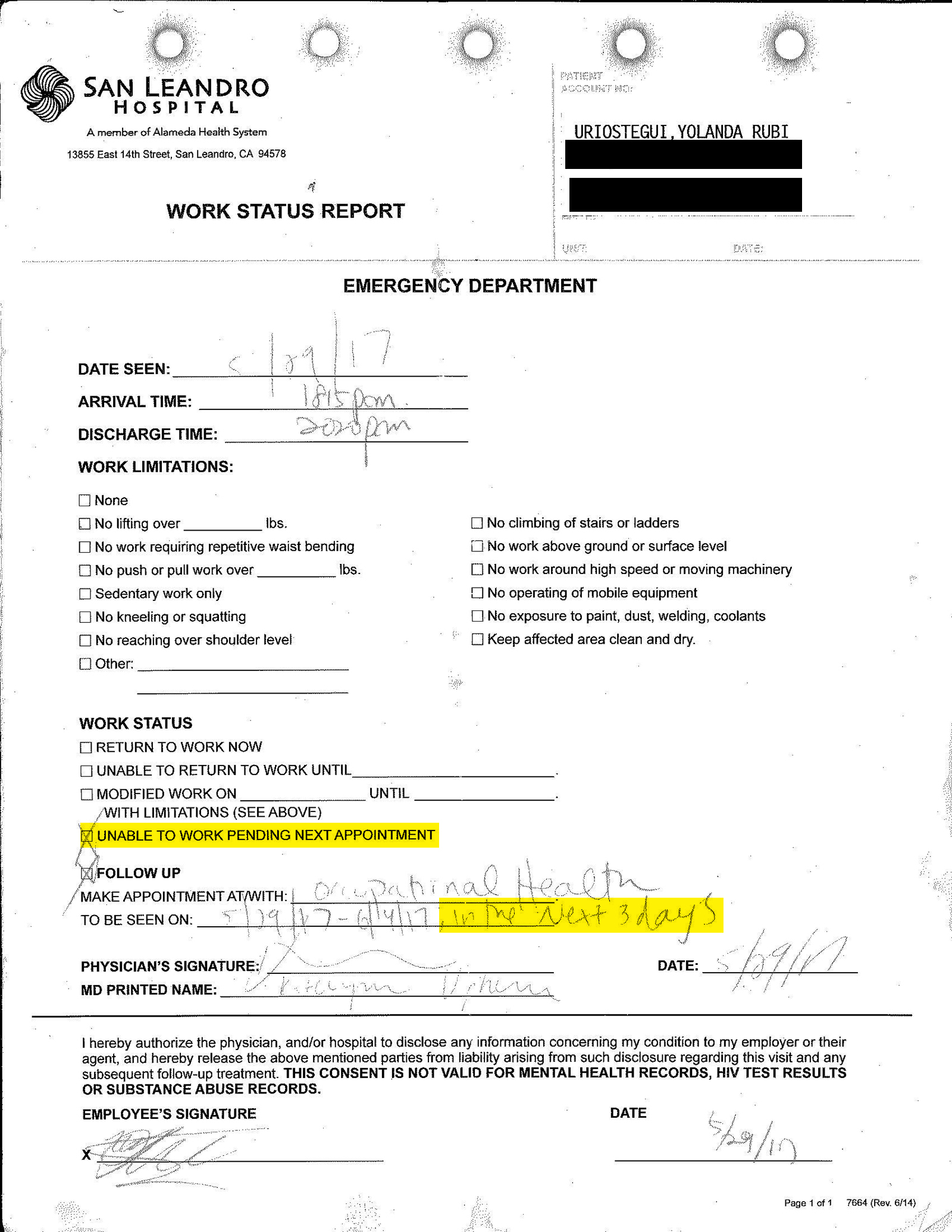

Urioste knew that she shouldn’t be working. The doctor who treated her at the San Leandro Hospital emergency department on the day of her injury had given her a note stating she shouldn’t work until after a follow-up appointment three days later.

Although she gave the letter to her KBS supervisor the day after her injury, Urioste said he ignored the request, and she continued on her normal schedule. Urioste, who is undocumented, feared that if she lost the job, she’d have no way to take care of her daughter. She ended up developing an infection on her toe, swelling in her knee and pain in her hip.

Her toe eventually healed, but the pain in her knee, hip and fingers was more persistent. After a string of doctor visits and recommendations that she take some time off to recover, in May, 2018, she finally asked her supervisor if she could work a less rigorous schedule.

Both she and Pedro say they were fired not long after that conversation.

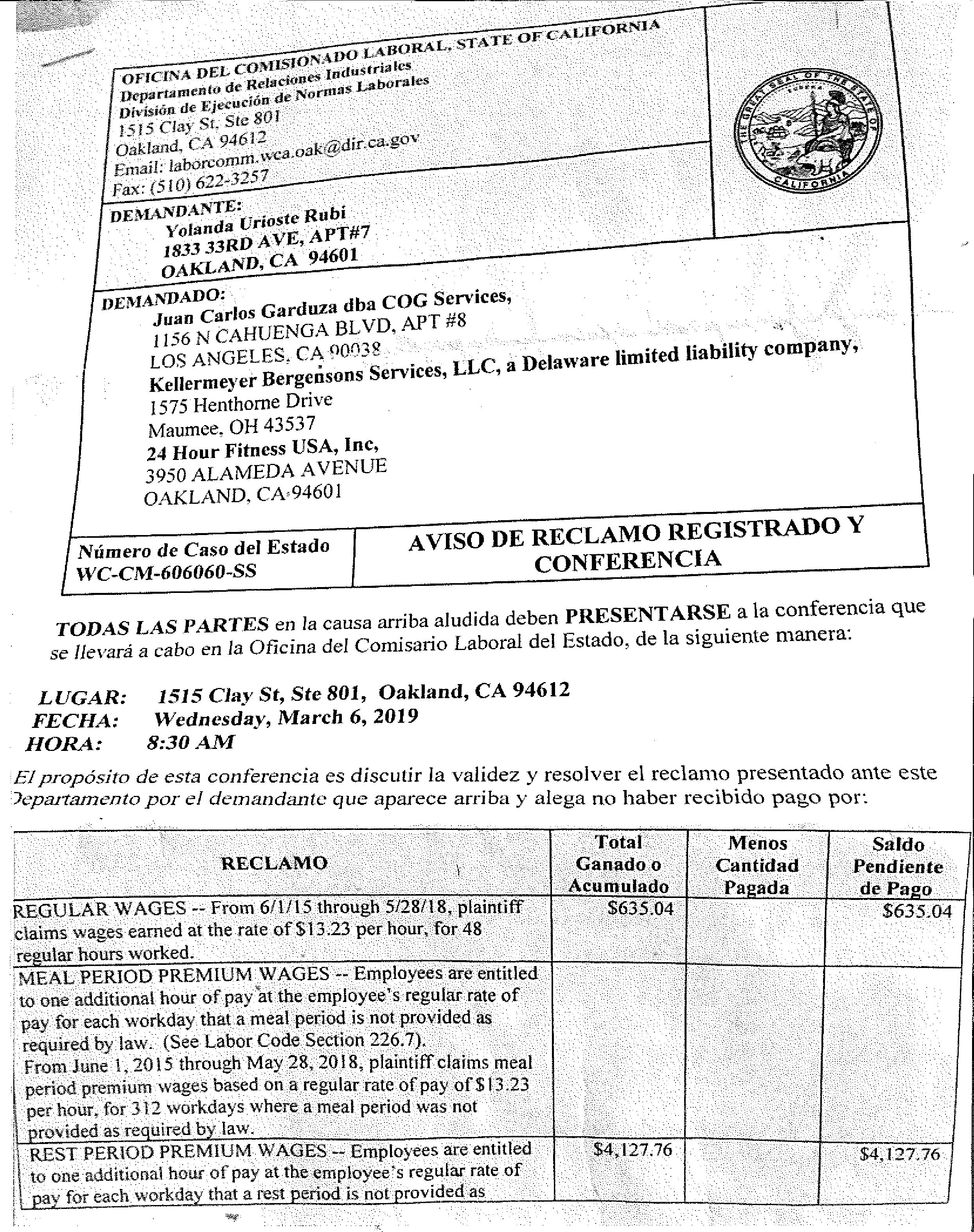

Later that year, Urioste filed a claim against KBS with the California Labor Commissioner—whose office enforces labor laws—alleging that the company had committed wage theft, the illegal practice of denying wages owed to employees.

Her attorney argued that the company withheld her last paycheck after she was fired, violated minimum wage laws and failed to provide rest periods during more than 300 days of work.

Urioste settled the claim in March for $8,000 and is now pursuing a workers’ compensation case through the Division of Workers’ Compensation. This process will determine whether her employer’s insurance provider will pay for expenses related to her work injuries.

Urioste and her attorney allege that, after being informed about her injury, KBS ignored its legal obligation to provide her with the paperwork to start a workers’ comp claim, which led to her claim being rejected for being filed too late. They believe she should be able to go through the claims process even though the incident happened two years ago.

KBS representatives didn’t respond to numerous phone and email requests for comment.

Lawyers and advocates who work with California’s undocumented workers say situations like these are all too common after workers report an injury. And so are complaints about employers refusing them workers’ comp.

"We've seen employers basically either telling workers to not report or 'You don't have access, you're not eligible for [workers’ comp],'” said Kevin Riley, director of research at the UCLA Labor Occupational Safety and Health Program. “We've heard stories about workers getting injured and being dropped off at a hospital and then the employer just disappearing, never to be seen."

But because this is a seldom-researched topic—under California policy, state agencies don’t keep data on workers’ immigration status—there are just a handful of studies documenting the problem’s scope, including one that Riley co-authored. That 2015 analysis found that 62 percent of 276 low-wage workers interviewed by an MIT research team in Los Angeles had received negative reactions from their employers after informing them of an injury. Those reactions ranged from demands to continue work and refusals to help to threats of deportation and termination.

Of the injured workers interviewed, fewer than 8 percent received workers’ comp to help pay for medical bills and 90 percent had an employer who committed a workers’ comp violation, such as failure to accurately complete the necessary paperwork. In California, these violations are criminal offenses and can lead to 60 days in jail and up to $10,000 in fines.

Almost 60 percent of the Los Angeles workers surveyed identified themselves as undocumented, and the study found that this group suffered from significantly higher rates of serious occupational injuries.

According to Riley and researchers at the UC Berkeley Labor Occupational Health Program, the data collected from the workers in Los Angeles offers a snapshot of the experiences faced by undocumented communities in cities across the state.

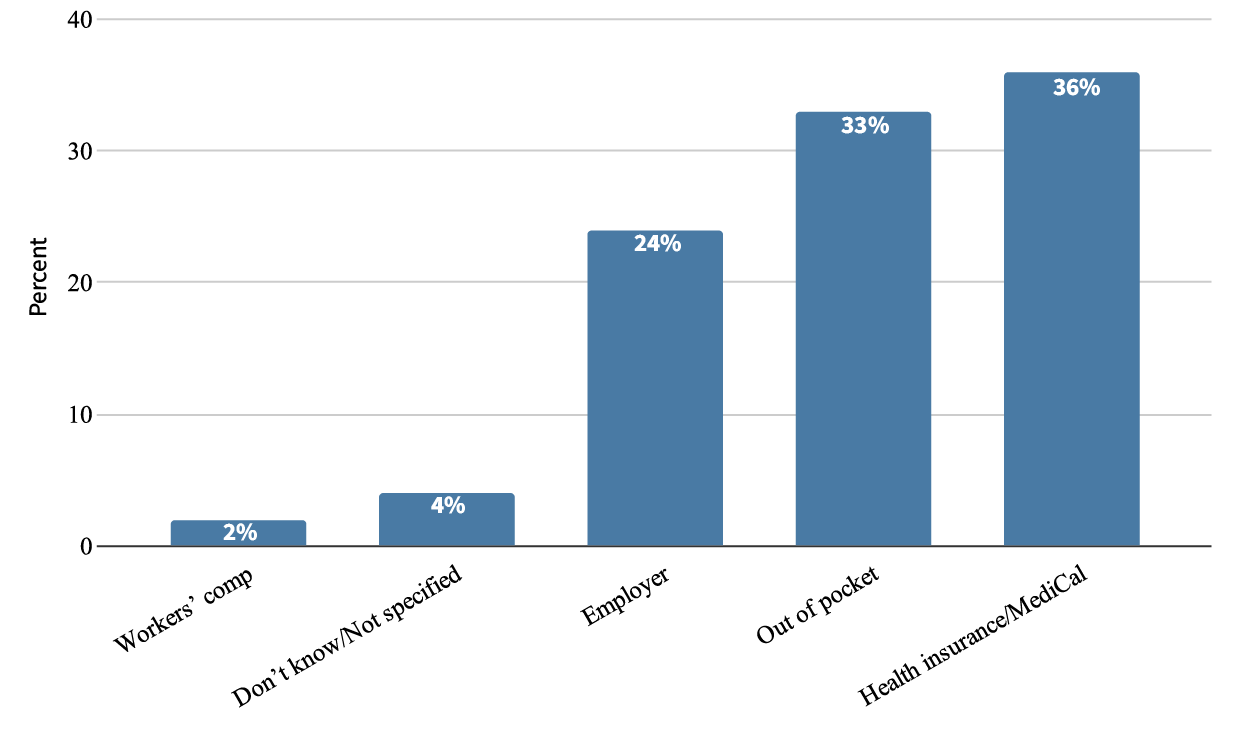

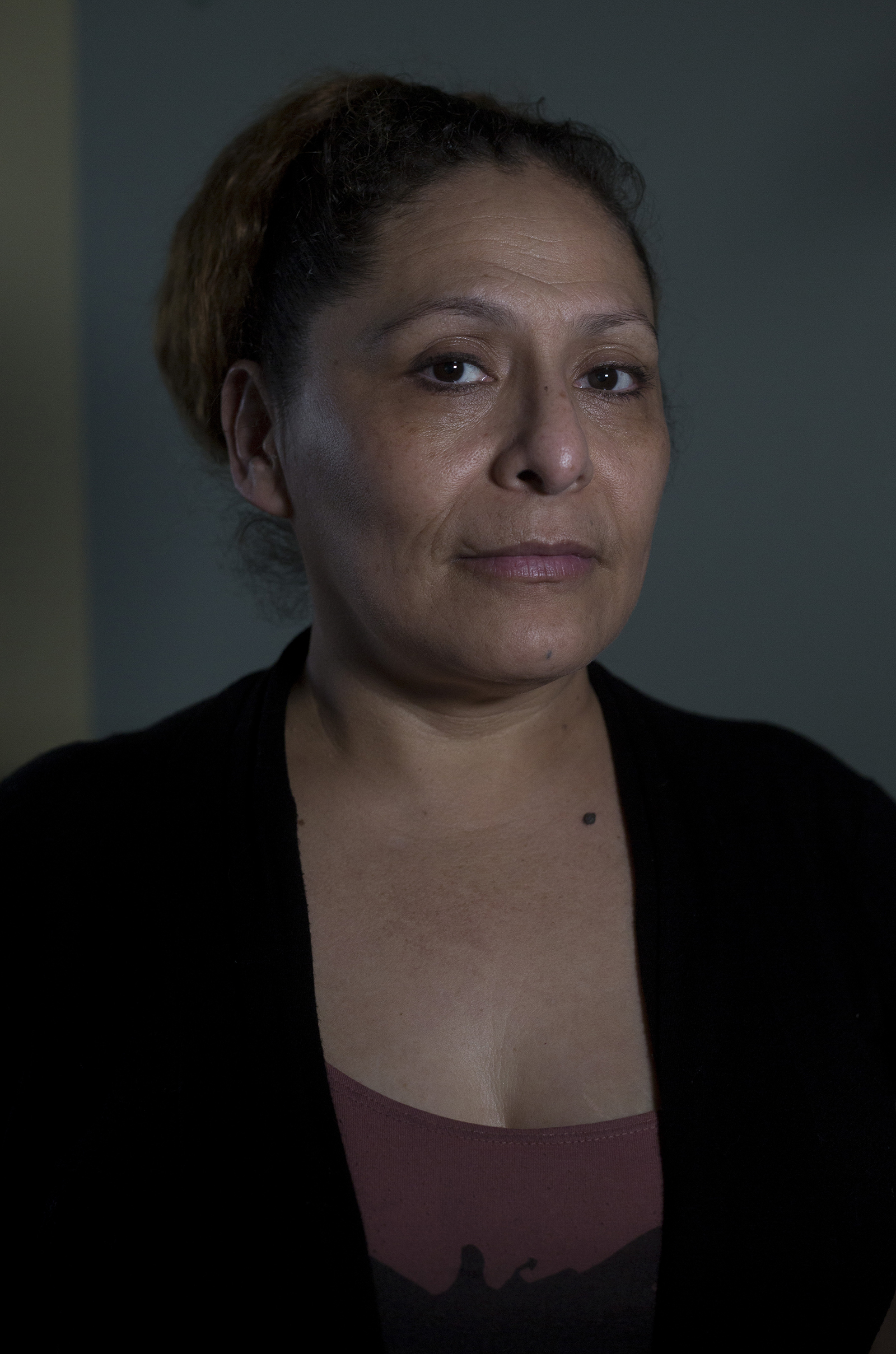

Yolanda Urioste sits at her kitchen table in Oakland, California. After losing multiple janitorial jobs due to physical ailments, she hopes to find work that is less physically demanding, such as cleaning offices. (Photo by Anne Wernikoff)

By April, although Urioste had received word that KBS was willing to settle her wage theft claim, she was still fighting the company for time and money she lost because of the injury.

She took a slow, deep breath as she sat down at her kitchen table and pulled out a plastic bag full of medical records and letters from lawyers. As she flipped through the pages she would often grimace, pain from years of repetitive stress injuries radiating up through her fingers and into her arms.

Then she pulled out a large white envelope from Gallagher Bassett, the workers’ comp insurance provider for KBS. The letter inside stated that her workers’ comp application had been denied because she didn’t notify her employer in a timely fashion about her injury.

Urioste and her attorney say she promptly informed her supervisor about her injury, but never received paperwork KBS was obligated to provide that would have allowed her to start a claim. “I told them that my injuries were very bad, I sent them pictures and they didn’t listen to me,” she said.

For many undocumented workers, this letter would be the end of their attempt to navigate the exceedingly tricky workers’ comp system. But Urioste had no plans to back down and her attorney was confident that her paper trail of medical records would give her the upper hand. They were planning to appeal the decision in the hopes of winning enough to pay her medical bills and get her back to work.

Rene Muñoz, an Oakland-based workers’ comp attorney who often represents employees like Urioste, said that if an undocumented worker considers taking the big step of pursuing a claim, the first hurdle is overcoming fears related to immigration status. Muñoz, who previously worked as a defense attorney representing companies in workers’ comp cases, says this issue has gotten worse in recent years as fear of deportation has increased under the Trump administration.

“One of the things that so many of my clients tell me is, ‘I don't want any problems’,” he said. “That's all I hear. ‘I don't want to get in trouble.’”

In some cases, when a worker does manage to submit a claim form, they speak with a claims adjuster—the insurance company employee who investigates claims to determine an employer’s liability. Only a worker’s physician can diagnose or modify medical treatments, but a claims adjuster can approve medical treatment requests made by physicians. Maria Sager, a workers’ compensation lawyer with Boxer & Gerson who has almost 20 years of experience representing Bay Area workers, says many of her clients contact her because an adjuster would not approve a simple medical test or standard medication. She's often heard of adjusters diagnosing medical problems despite not being trained to do so, and seemingly obvious injuries being put on 90 day holds "to investigate" even when employers don't raise an issue.

“There is often an attitude expressed, explicitly or implicitly, that your injury is not that serious or your doctor should send you back to work,” she said.

Workers whose claims are accepted will receive medical treatment, or undergo an evaluation if there is a dispute. The doctor’s evaluation of the severity of their injury determines how much they’ll receive from the insurance company to cover their medical bills. However, in a Medical Provider Network, they have to choose their doctor from a list of providers maintained by the insurance companies. Attorneys and labor rights advocates say this can lead to situations in which physicians give evaluations that are favorable to insurers in order to stay on their lists.

As challenging as it can be to navigate the Cal/OSHA world, workers’ comp is just a mess.

— Kevin Riley, director of research at the UCLA Labor Occupational Safety and Health Program.

The value of workers’ comp cases can range from a few hundred dollars to hundreds of thousands. In some outcomes, settlements can quickly add up for employers and insurance companies if they don’t get favorable evaluations. This increases pressure on doctors to downplay the severity of an employee’s injuries.

And because the doctors on these lists—known as Medical Providers Networks—are often backlogged, workers can wait for months before getting their evaluations. If an employee disagrees with their doctor's decision, they can seek a second opinion from another MPN physician. Riley says this forces many workers to turn to personal doctors or health clinics for help, and their cases never end up in the workers’ comp system. (A communications director at the Department of Industrial Relations disputes this, saying the Division of Workers' Compensation doesn't have evidence of employees waiting months for medical treatment.)

"From an injured workers’ point of view, that is a much more rational decision to make, because you can get care very quickly,” he said. “You don't have to wait for all these approvals to come through.”

While the majority of workers’ comp claims filed in California ultimately lead to some payout, Muñoz says his undocumented clients usually settle for far less than they’re owed because they’re afraid to apply for State Disability Insurance (SDI), the safety net that provides employees a percentage of their regular income when they miss time due to an injury. Most undocumented workers qualify for SDI, and Muñoz recommends they apply for the program to hold them over while they pursue a workers’ comp case. But this is easier said than done.

“Most of my cases take anywhere from a year to 18 months to really develop,” Muñoz said. “Let's say you have a really bad back injury that's maybe worth $50,000. Well, here’s a $15,000 [settlement]. Even though you advise against it, if they need the money, you can't really say much.”

And not all employees qualify for workers comp in the first place. California employees are eligible if they have worked 52 hours or more for an employer in the 90 days preceding injury, have earned $100 or more in wages, and whose employer is an owner or occupant of a residential dwelling. While a majority of California’s undocumented workers qualify under this criteria, many of the state’s estimated 40,000 day laborers, who are often hired by private homeowners for jobs that last a day or two, may not be eligible unless the employer's homeowner insurance covers this.

In 2018, Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, a Democrat from San Diego, authored Assembly Bill 206, which would have eliminated the 52-hour minimum and imposed a small fee on all homeowners to cover workers’ comp insurance. “You go down to Home Depot, and you hire somebody to come paint or whatever it is, and they end up injured,” Gonzalez said. “There's absolutely no recourse for them. And I thought it made sense to me.”

But the plan garnered little support among fellow lawmakers in Sacramento and died without receiving a hearing.

The researchers from UCLA’s Labor Occupational Safety and Health Program estimate that 34 percent of the 106 people they interviewed for a 2017 study about workers’ comp eligibility among day laborers would have gained access to the system had the bill passed.

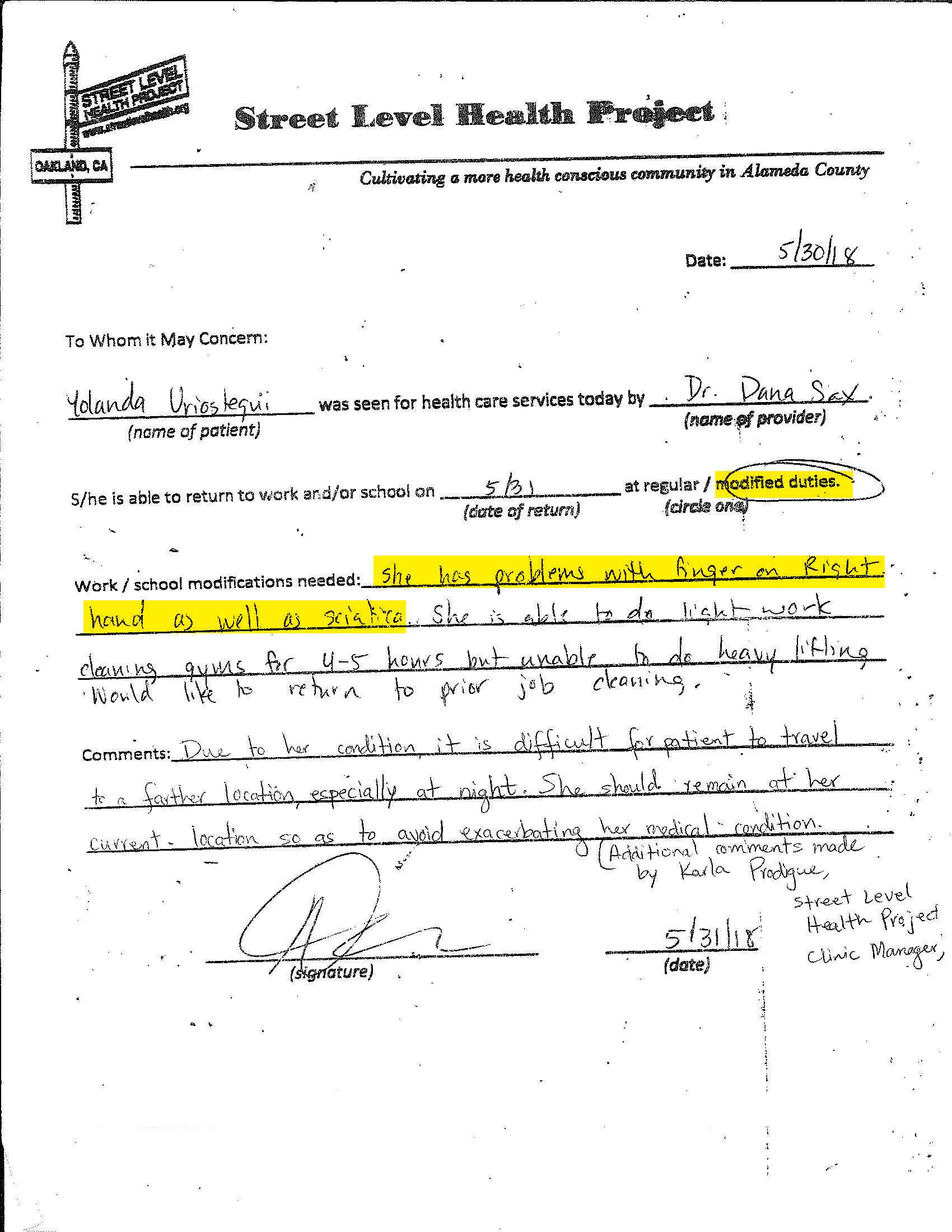

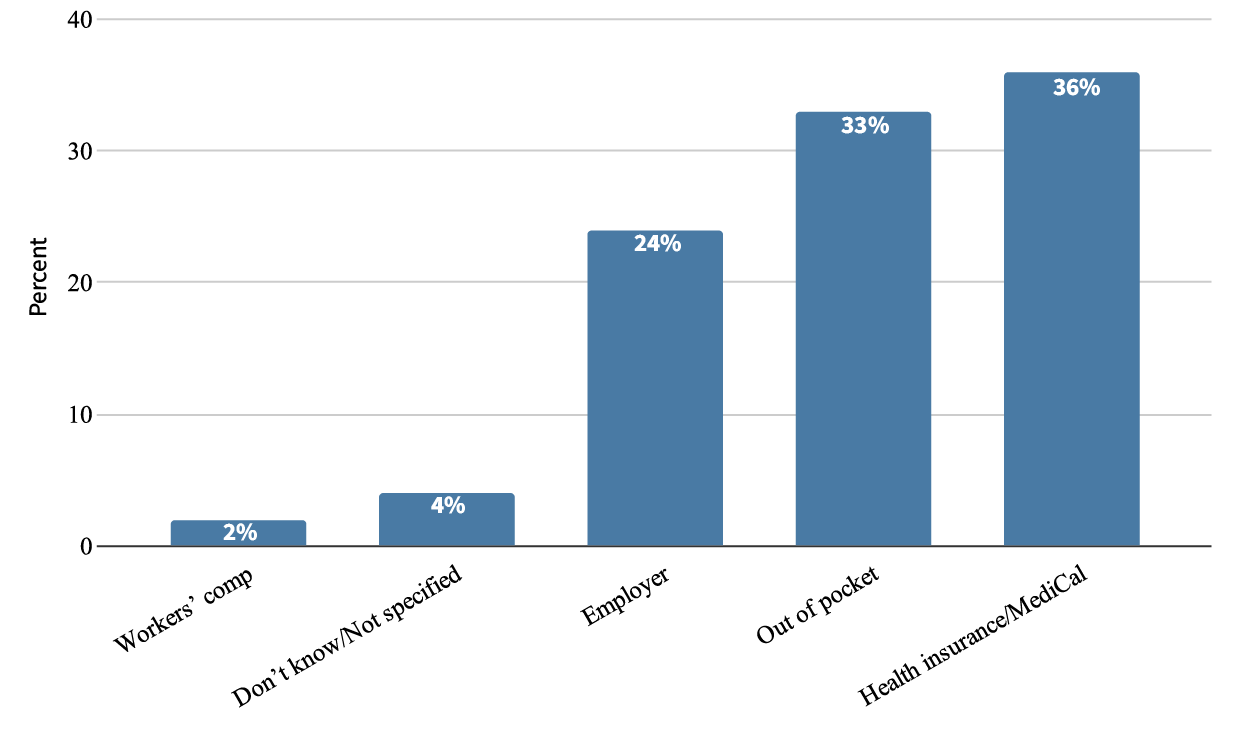

Most workers end up paying medical bills out of pocket or through Medi-Cal—meaning taxpayers are footing the bill instead of employers. The UCLA researchers found this to be the case for 70 percent of the workers surveyed.

Who paid for medical bills?

Source: UCLA Labor Occupational Safety and Health Program

“What that does is just shift the cost burden, which was supposed to be on an employer, and create a disincentive to reduce those injuries as much as possible,” Riley said.

Without workers’ comp, to pay her medical bills, Urioste has relied on a program called HealthPac, which provides insurance for Alameda County residents below the federal poverty level. She recently finished physical therapy on her right hand, but is still in constant pain.

Since being fired by KBS, she has been hired and let go from multiple cleaning jobs because her injuries don’t allow her to work at the fast pace employers demand. Without a stable job, she’s worried that once the $8,000 from the wage theft settlement runs out, she won’t have a way to pay her rent.

Yolanda Urioste, a janitorial worker, has suffered injuries to her foot, hand, back and hip from accidents and repetitive motion on the job. (Photo by Anne Wernikoff)

She’s hoping that her workers’ comp claim, which is still in the early stages of the appeal process, will just give her enough to pay for medical treatment and get back to work.

“I’m not asking for money. I’m asking for work,” she said. “I can still work. I can take it. I can bear the pain.”

For the rare undocumented worker like Urioste, who was willing to file both workers’ comp and wage theft claims, the process has been physically and emotionally draining. But she’s been willing to spend the time and money on them because she’s tired of staying silent due to her immigration status.

“I ask God that someone sees this and fights for justice,” she said. “Just like they've done to me, they're doing this to a lot of people who remain silent because of the same fear—that they're going to see their documents and see they are not legal.”

Retaliation and stolen wages

After arriving in California from El Salvador eight years ago, Lupe constantly struggled to make ends meet. But she, her husband and their two young kids were able to get by.

That all changed when her husband, who worked for a moving company, injured his back so badly he had to have two discs surgically removed. With him unable to work, Lupe found a job at a Bay Area car wash through a temp agency. (We are not identifying Lupe by her full name due to a non-disclosure agreement that restricts her from speaking publicly about her former employer.) She worked 10 to 16 hours a day, earning $3 for each car she finished and never receiving overtime. She knew her employer wasn’t paying what she was owed, but as an undocumented worker felt there was nowhere to turn.

“I did not want to go to work, but I had to go to work for my children,” she said.

Lupe, a former car wash employee, faced retaliation and harassment from her employer after taking a business card for an OSHA inspector. (Photo by Anne Wernikoff)

Lupe says the job went well for the first few months, but her relationship with her employer quickly deteriorated after a coworker quit and reported health and safety violations to the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA). An inspector soon arrived at the facility, taking note of a leaking roof that was at risk of collapsing, inoperable bathrooms, and slick floors that had led to numerous employees falling.

“The OSHA people said there had to be floor mats to keep us from slipping, that people had to work in proper uniforms, with the right shoes,” she said. “[My employer] did not give us a uniform or shoes.”

The inspector left his card with a few other employees and Lupe decided to ask them for his number. Three days later, she said, her manager angrily called her into his office.

“He told me that I had a lot to lose because if OSHA came they would ask for my papers and that he knew I was going to be deported,” she said.

In truth, Cal/OSHA doesn’t coordinate with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement or ask employees to report immigration status. But fearing deportation, Lupe continued working at the car wash until months later when her husband was badly injured in a fight following a car accident. When she asked the same manager for time away from work to help her husband file a police report, she said she was again threatened with deportation.

At this point, at the recommendation of a friend, she quit and reached out to an attorney at Centro Legal de la Raza, a legal organization focused on protecting low-income, Latino communities. Lupe and her attorney filed claims of retaliation and wage theft against her employer through the Labor Commissioner's Office, arguing that her employer harassed her due to her immigration status and stole overtime wages by withholding them.

They successfully negotiated a settlement that awarded her about $15,000, almost all of which was for the retaliation claim. However, the settlement also came with a non-disclosure agreement. Under the terms of the agreement, she can speak to state agencies like Cal/OSHA about the company, but only if they initiate the conversation. And she cannot warn people in her community about the dangers of working at the car wash.

“You feel like you have your hands tied,” Lupe said. “Because sometimes you would like to say what company it is, so other people do not go there, but I cannot do anything.”

Now that Lupe's husband has returned to work, she stays home to care for their two young children. She hopes to one day start a business as a makeup artist. (Photo by Anne Wernikoff)

According to Deylin Thrift-Viveros, a former attorney with Central Legal de la Raza who represented Lupe, non-disclosure agreements are an unfortunate, but often necessary, tool for getting workers the money they need to survive. And for most undocumented workers, the risks of filing an OSHA claim—where fines go into the state’s coffers rather than back to employees—far outweigh the rewards.

“Confidentiality agreement is the quickest way to resolution. It's a common device in these kinds of agreements,” he said. “We always try to push back on the confidentiality, of course. But, if we want to resolve the case quickly, it depends on the client.”

Despite receiving a settlement, Lupe is disturbed that the visit from the OSHA inspector seems to have done little to change working conditions at the car wash. Lupe has heard from former coworkers that the roof has been repaired, but other fixes, like addressing the slippery floor, have not been made. The carwash is still operating in the same location but under a different name.

I still feel afraid, because I do not know if that person can follow me. And I feel that fear that, maybe just for not having papers, he can do something.

— Lupe, undocumented worker.

Cal/OSHA records show that, under its old name, the business received a fine of roughly $7,000 for not providing employees with eyewash equipment and maintaining sanitary work conditions.

But Lupe’s coworkers were lucky that the car wash got inspected at all. Cal/OSHA currently staffs just one field inspector per 87,000 workers, which means many bad actors operate with impunity.

In response to a question about the inspector-to-worker ratio, Frank Polizzi, a spokesperson for the Department of Industrial Relations, which oversees Cal/OSHA, wrote that the agency makes every effort to use its resources wisely.

“Cal/OSHA’s district and regional managers have the ability to deploy inspectors from other districts and regions across the state when needed to assist inspectors in a given district,” he wrote. “Cal/OSHA is engaged in training all enforcement staff to consistently and effectively enforce California’s workplace safety and health regulations.”

When Cal/OSHA does pursue a case against an employer that has violated safety laws, it issues penalties based on a variety of factors including the employer’s size and whether it has been cited for a similar violation within the previous three years. Labor advocates argue, however, that these fines are often too low to act as a deterrent against future dangerous behavior.

“OSHA citations, I mean they're really laughable,” said Nicole Marquez, a staff attorney for Worksafe, an Oakland-based legal support organization. She mentioned a case in Orange County where two workers were killed by an exploding water pipe and the total sum of the OSHA penalties was $90,000.

Because the car wash is still operating, Lupe lives with constant anxiety that her former employer will still feel emboldened to retaliate against her.

“I still feel afraid, because I do not know if that person can follow me,” she said. “And I feel that fear that, maybe just for not having papers, he can do something.”

The most vulnerable

On a chilly Monday morning, Abad Leyva and two other staff members from the Oakland Workers’ Collective loaded up a pickup truck with peanut butter sandwiches, oranges and coffee and headed down International Boulevard, one of Oakland’s busiest streets.

As they pulled to a stop by the empty parking lot of a Mexican seafood restaurant, 20 or 30 men in work clothes and boots walked up to the truck, eating food while listening to the staff talk about the services the collective offers to day laborers. The Fruitvale-based day labor center is part of Street Level Health Project, a community organization that provides recently-arrived immigrants with free health clinics, occupational safety training and assistance with workers’ comp and wage theft cases.

“We have a responsibility with them—a moral responsibility, a family responsibility—to tell them, you have rights, you can make them valid, there are ways for you to get better jobs,” Leyva said.

Leyva, noticing a few men who stayed on the opposite end of the parking lot, grabbed a handful of informational pamphlets and jogged off to talk with them. Over the course of an hour and a few more stops, Leyva and his team spoke to more than 100 day laborers with the hope a few would show up at the collective’s weekly meeting.

Leyva, with his head of curly brown hair, is a well-known figure in Oakland’s day labor community. Over the last year, he has worked as the collective’s labor rights organizer, but his experience stretches back over a decade of activism in the region.

Former day laborer Abad Leyva meets with a client at Street Level Health Project where he works as a program manager promoting immigrant rights. (Photo by Anne Wernikoff)

After arriving in Chicago from Mexico as an undocumented immigrant in the late ‘90s, Leyva moved to Oakland in the hope of building a career as a filmmaker. After a divorce left him severely depressed, he quit school and started working as a day laborer, finding jobs online or through word-of-mouth.

Leyva says it’s hard to compare the experience of working as a day laborer to anything else he’s done, other than crossing the border into the U.S. “If you're a day laborer, you go to work but you're not a human,” he said. “You know, you're just an instrument to clean or to organize or to do something.”

While he was never seriously hurt on the job, Leyva often found himself in dangerous workplaces with little or no safety instructions or protective equipment. One workplace that is burned into his mind is a metal shop he was hired to clean. Leyva says the air in the shop was often full of aluminum dust, which can cause scarring of the lungs, leading to coughing and shortness of breath. While the full-time employees were provided with masks and gloves, the undocumented workers only received equipment when the supervisors knew a city inspector was stopping by.

“It is a game, man. It's just the freaking mentality that you have to compensate, you have to extra-compensate, for what you're lacking,” he said. “The fact that you don't have documentation it makes you go and do this kind of stuff.”

While there are few studies that specifically focus on the safety of undocumented workers, there are many that focus on the kinds of jobs they hold, specifically jobs often worked by Latino men. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Department of Industrial Relations, construction—a workforce that is 48 percent Latino and 42 percent immigrant—has the fourth-highest rate of worker fatalities in California. Other jobs commonly filled by undocumented workers, like grounds maintenance workers and painters, also rank in the top 10 for most dangerous in the state.

A 2015 report issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control highlighted three factors that leave Latino immigrant construction workers particularly vulnerable to injury: a lack of knowledge about job risks and standard safety procedures, language barriers between workers and their supervisors, and a willingness to engage in risky behavior in order to be perceived as hard workers.

None of these statistics would come as a surprise to Leyva, who often counsels workers who’ve come to the collective after suffering devastating injuries. He is currently advising a worker who broke both of his feet after falling off a ladder while painting. Leyva says that in cases like this, if the worker’s effort to get compensation for his medical bills fails, the injury can sink a family for a whole generation.

“How in the heck are they going to pay rent?” Leyva asked. “I'm pretty sure that mom is going to start working, and she's going to work 20 hours a day because she needs to.”

“And,” he added, “the kids are going to be raised by—hopefully—the community.”

What can be done

On April 3, sitting in a State Capitol hearing room surrounded by dozens of supporters, Assemblywoman Gonzalez launched into an impassioned speech about Assembly Bill 5, her newest piece of proposed legislation that could potentially help undocumented workers.

The bill would codify into law a 2018 California Supreme Court ruling that expanded the number and type of workers who have to be recognized as employees, instead of independent contractors. Commonly known as the “Dynamex decision,” named after the delivery company that was sued for classifying its drivers as contractors, this ruling could go a long way toward reducing the prevalence of worker misclassification. This is practice by which employers classify their workers as independent contractors to avoid paying benefits and liabilities if they get injured.

“This is our opportunity to make it clear every working Californian, every single working Californian, deserves basic protections that allow them to support their family,” Gonzalez said. “People should not have to rely on the emergency room when they get injured on the job and should not be starting GoFundMe pages to finance their medical bills.”

While this issue has gained attention in recent years with the rise of gig economy giants like Uber and Lyft—which classify their drivers as contractors—fields like construction and janitorial work have had problems with misclassification for decades, Gonzalez said.

The new law uses a test to determine a worker’s classification. To be classified as contractors, workers must be able to perform their work without directions from the employer, and the work has to be different from the employer’s business. Construction workers building a house and janitors doing cleaning work can’t be deemed contractors under these rules.

The bill is currently moving through the state legislature. If passed, it would become law on the first day of 2020.

Over the last few months, Leyva has told as many undocumented workers as possible about the effect this new standard could have. “It will be a really good tool to avoid that misclassification of people and it will protect people who many times, also, are paid not even minimum wage,” he said. “It will mean so much peace for these people.”

Cal Soto, the workers’ rights coordinator at the National Day Laborer Organizing Network, believes Dynamex was an important ruling for protecting workers, but California should also take cues from safety programs in other states. He points to New York City, where the high-profile death of a 22-year-old undocumented construction worker in 2015 led to the creation of a mandatory 10-hour OSHA training program for construction workers that has been seen as a huge success in that industry.

“They upended their training structure and, in doing so, put a lot of resources and funding behind making sure those workers could get trained,” Soto said. “They put their money where their mouth was.”

When asked about programs the Department of Industrial Relations has enacted that support workers, Polizzi pointed to a campaign launched in 2014 to fight wage theft. He didn’t highlight any initiatives that specifically focus on health and safety.

Gonzalez, who was a labor organizer before becoming a politician, is hopeful a more progressive state administration under Governor Gavin Newsom will lead to increased funding and staffing at the agency, so it can create new education programs and step up enforcement. But, until that happens, she feels California is falling short of its responsibility to protect all workers.

“Our state legislature is a national leader in establishing the country's strongest workplace protections,” she said. “But if companies evade their obligation as employers without consequence, then these laws become worthless.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the acronym for Cal/OSHA as California Occupational Safety and Health Administration. The correct name is California Division of Occupational Safety and Health.

Liliana Michelena contributed to this story. Susie Neilson provided research.

UNSEEN

WORKING IN THE SHADOW OF THE GOLDEN STATE

Uneven Ground

Women make up just 3% of lucrative male dominated construction jobs – Gender based harassment and discrimination has kept their numbers virtually unchanged half a century after affirmative action.

Pennies per Hour

Most California state prisoners hold jobs that maintain prison facilities for as low as 8 cents an hour. The roles are cost-effective for the state, but critics say they don’t prepare inmates for life on the outside.

NEW PATH

More than 600,000 inmates are released from prison every year, 35,000 in California. Most are seeking a regular job that can keep a roof over their head - a challenge that’s not easy to overcome.

SMOKE AND MIRRORS

Cannabis legalization in California is a mess. Tax revenues are lower than expected, the illegal market is thriving and workers on the Central Coast are weighing the benefits and fears of working in a newly permitted industry.

STOLEN

In California, wage theft is underreported, underenforced, and costs workers billions of dollars every year. But, you’re more likely to be prosecuted for stealing a sandwich.

SECOND CLASS

California’s almost 2 million undocumented workers face a disproportionately high risk of being killed or injured on the job despite state laws designed to protect them.

ON THE LINE

California has some of the nation’s most progressive recycling policies and goals, but the industry’s workers face hazardous conditions—and global market forces are adding to their strain.

DIRTY BUSINESS

Workers in California’s waste industry labor far beyond our shores. Plastic recyclers in Minh Khai, Vietnam wrestle with the blessings and curses of an empire built on our trash.

Read her claim

Read her claim