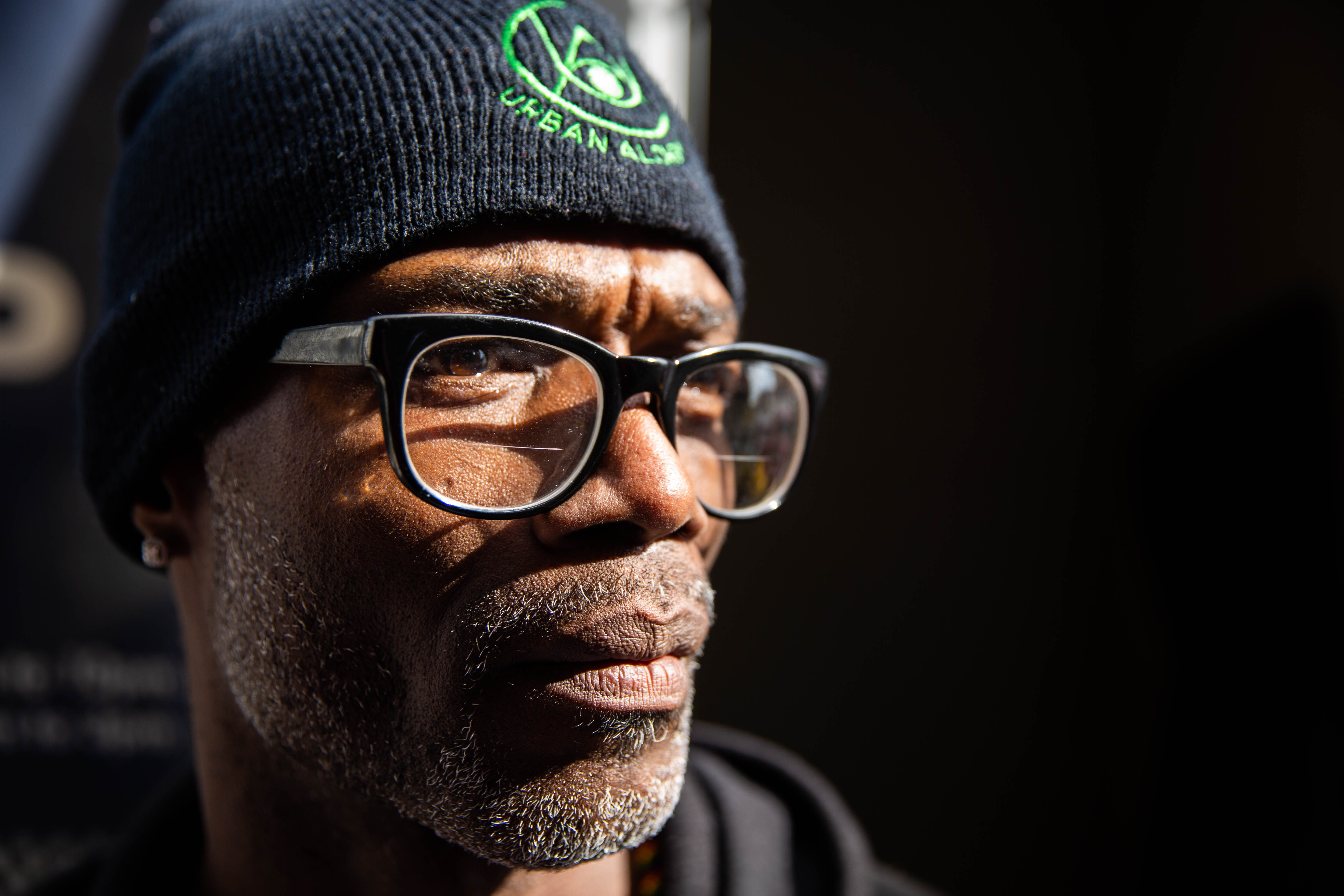

Anthony Bustos started to work for Pit Stop last year, about six months after his release from a California state prison. When the 43-year-old gained freedom after 22 years of incarceration, he wanted to open up and talk to people. He says getting the job gave him the opportunity to do that.

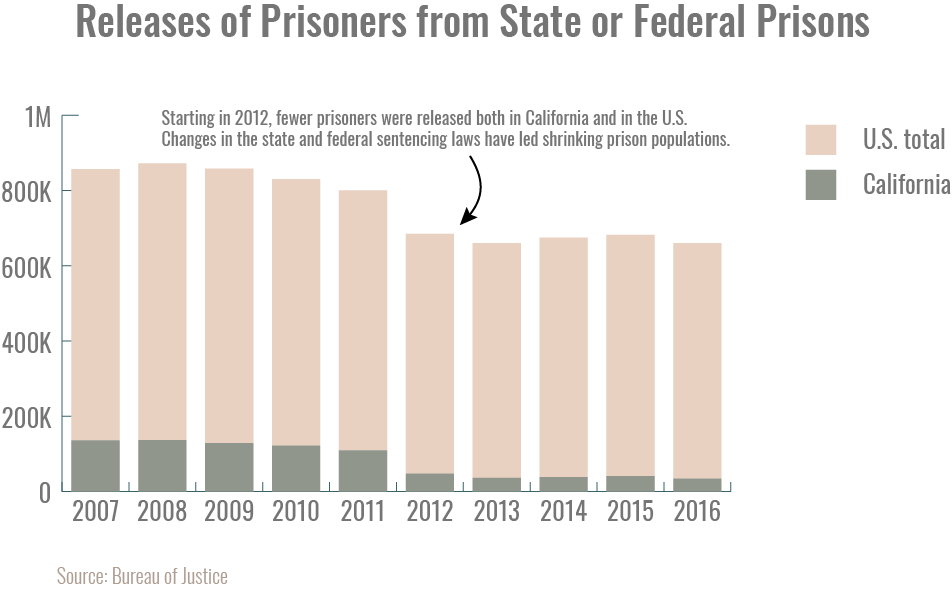

Bustos is among the 95% of state prisoners who won’t have to spend their lives behind bars, according to the Bureau of Justice. However, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) doesn’t track the employment of former prisoners. Only a few small-scale studies show their struggles: In a survey of 101 residents of West Contra Costa County who had been released within the previous 3-18 months in 2011, 78% of respondents were unemployed. Nearly all the respondents with a job were working part-time in construction, auto repair or other forms of manual labor.

Convicts are released either into state supervised parole, as was Bustos, or county-level supervision (also knowns as post-release community supervision), according to CDCR. The most serious and violent offenders are released to state parole, and the non-serious, non-violent, and non-sex offenders are released to county-level supervision. Parolees are assigned a parole agent and obligated to follow their agent’s instructions. Former inmates who are under county-level supervision are supervised by a local law enforcement agency. Parolees account for half (49.3%) of those released from state prisons in 2017, the most recent year available, according to CDCR. Their average length of stay in prison (4.7 years) is almost four times greater than that for those under county-level supervision (1.3 years). After their release, parolees are required to attend a “Parole and Community Team (PACT)” meeting to learn about community resources, including employment opportunities.

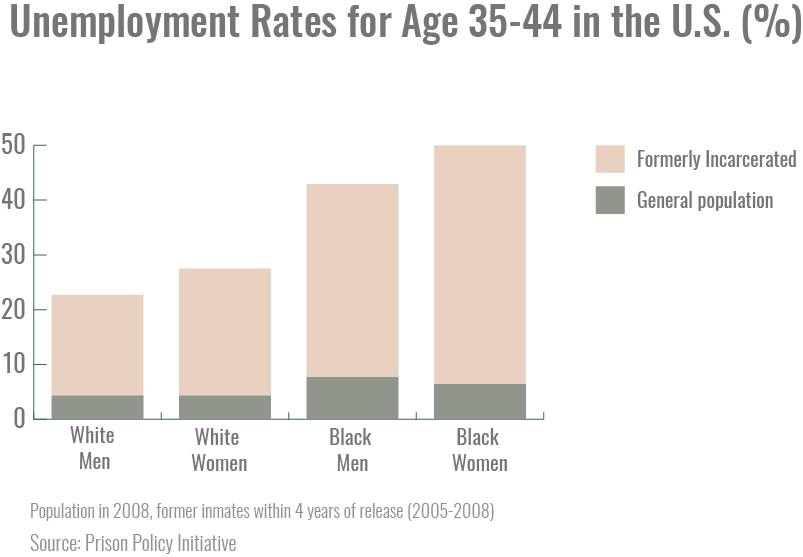

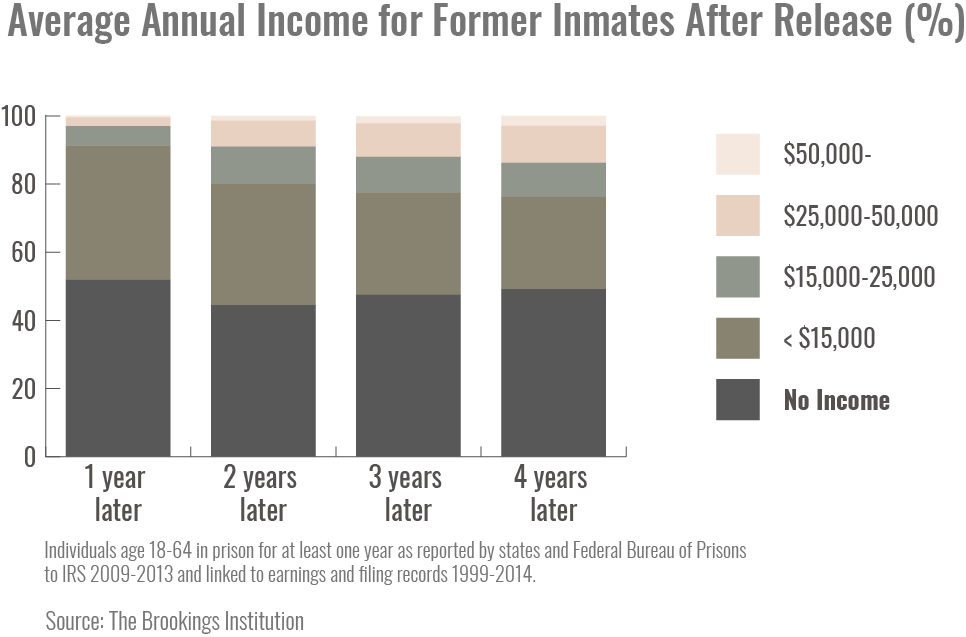

Getting a job after many years behind bars is not easy. Many former inmates lack skills and work experience. Some prisons have robust job training programs, but only a handful of prisons make a real investment in that area, says Lonnie Tuck, Regional Director of Oakland’s Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) Office.

“We have a lot of untapped potential but we don’t engage in the vocational training and education that we should to make sure that people come out actually stronger and better as opposed to worse.” – Katherine Katcher, founder and executive director of Root & Rebound, a reentry advocacy organization

A criminal history historically has been a barrier to employment. To address that problem, the Fair Chance Act, which prohibits employers with more than 5 employees from asking about a candidate’s conviction history before making a job offer, went into effect in California last year. However, people are still often asked about their convictions in interviews because a lot of employers don’t know about the law, says K.C. Taylor, associate director of California Legal Services.

Fields that require occupational licenses - everything from barbers and cosmetologists to insurance sales agents and dental hygienists - have been especially challenging for former inmates. More than 25 percent of the American workforce is in licensed positions, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Licensing is a state responsibility. Some state laws prohibit people with criminal records from licensed jobs, or they require “good moral character,” which has been interpreted to ban individuals with criminal records, according to a report published by the organization. “Over the years, we saw how the licensing agencies would routinely deny clients with a criminal record regardless of how old the conviction was, how minor it was, and if it was not related to the type of job,” says Vinuta Naik, staff attorney of the East Bay Community Law Center (EBCLC).

In California, Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law Assembly Bill No. 2138 (AB 2138) last year. It will prohibit licensing agencies under the Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA) from denying licenses for convictions more than 7 years old unless the conviction was for a serious felony or a financial crime, when it takes effect in 2020. However, the bill only applies to boards under DCA and other boards, such as the Department of Social Services (caregiving), Department of Insurance (insurance agents), emergency medical technician (firefighters and paramedics), and the bar (lawyers), are not covered. “The other boards need to change as well to allow a fair chance to all people,” says Naik.

Having a job is closely related to whether a former inmate will commit another crime and be returned to prison.

“If people do not have jobs, if people cannot earn money legitimately, if people cannot take care of their families, if people just feel that they are worthless, then I think you see more crime.” –Mohammed Nuru, director of San Francisco Public Works

Nearly half (46.1%) of former inmates are convicted of a felony or misdemeanor offense within three years of their release from state prisons, according to CDCR.

David Harding, a professor of sociology at UC Berkeley who studies social and economic reintegration of former prisoners, says that “social connections,” such as a job referral or support from family, have a big impact on former inmates’ employment. “In our study, the only people who were successful at not just finding a job but a job that paid a living wage and had a career ladder attached to it were people who were able to get access to those jobs through their social connections,” he says. “But of course, most prisoners are coming from families that don’t have those kinds of economic and social resources.”

A transitional job is useful because it helps former inmates rebuild their lives, Harding says. “Certainly, people coming out of prison are really eager to work,” he says. “People are really looking for a way to construct meaning for their lives and feel like they are contributing in some ways. I think in that sense, it’s useful just for that.”

There are several programs that offer transitional jobs to former inmates. The Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) offers enrolled participants a short-term transitional job where they work up to 4 days a week and earn daily income. During that time, participants work with CEO regularly to prepare job applications, and move on to full-time employment. The participants were 52% more likely to be employed than their counterparts in the comparison group, according to the organization’s 12-month post-enrollment evaluation.

Other organizations run transitional jobs program throughout the country, such as Safer Foundation in Illinois and Project Return in Tennessee.

One program designed to help inmates and meet a community need is the Pit Stop program in San Francisco.

San Francisco Public Works partnered with two nonprofit organizations to staff the city’s public toilets as part of a workforce development program. Hunters Point Family, a nonprofit organization that provides various programs including workforce development, staffs 24 locations, and Lower Polk Community Benefit District, a nonprofit organization that works to improve the lives of people in the Lower Polk community of San Francisco, staffs one.

The location of Pit Stop toilets in San Francisco.

The Pit Stop program began in 2014 as a six-month pilot project at three locations in the Tenderloin after a community budget hearing. Students from the De Marillac Academy said that they were tired of having to navigate around human waste on their way to and from school in the Tenderloin. Nuru convened a meeting with his staff, and they came up with the idea for Pit Stop. It aimed not only to solve the community problem but also to create a pipeline for people trying to re-enter the workforce.

The program was started with other nonprofit organizations to staff the toilets with people from different backgrounds. Then San Francisco Public Works formed a partnership with Hunters Point Family in 2016 as the program grew, and former inmates began to be hired. It now operates at 25 locations with an annual budget of $3.1 million, and about 150 employees. “The partnership with the Hunters Point Family is a very powerful partnership for the Public Works department in a sense that they are able to help us hire a lot of these individuals who try to change their lives,” says Nuru. “We provide the funding, we provide the equipment, they provide the people.”